The European RoHS Directive (RoHS = Restriction of Hazardous Substances) regulates the restriction of hazardous substances in electrical and electronic products. Although it is a fairly old European directive, it is becoming increasingly important in light of the growing sustainability and environmental debates.

In line with the European Union’s new approach (New Legislative Framework), the RoHS Directive is one of the CE directives and requires the CE mark to be affixed to the product. In Germany, it is transposed into national law by the Electrical and Electronic Equipment Ordinance (ElektrostoffV).

Questions about the scope of application of the RoHS Directive and, in particular, the exemptions are among the most frequent concerns that companies and customers bring to us.

The directive limits the use and regulates the limit values for currently 10 different substances and specifies their limit values, including 4 heavy metals, 4 plasticizers and 2 flame retardants:

Cadmium (Cd)

lead (Pb)

Mercury (Hg)

Hexavalent chromium (Cr VI)

Polybrominated biphenyls (PBB)

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE)

Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP)

Benzyl butyl phthalate (BBP)

Dibutyl phthalate (DBP)

Diisobutyl phthalate (DIBP)

The limit values for all substances are 0.1% by weight, with the exception of cadmium, which is limited to 0.01% by weight.

The areas of application of the substances mentioned vary. The best known are lead in solder, mercury in mercury vapour lamps and the four different plasticizers in many types of plastic or rubber, e.g. in shrink tubes.

This includes any device that is dependent on electric current or electric fields for at least one of its functions. This includes, for example, televisions, refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, shavers, electrically operated toys or computer mice.

Gas stoves with electric clocks, armchairs with electrically adjustable footrests, e-cigarettes and clothing or shoes with light effects must therefore also meet the requirements of the RoHS Directive. Whether the product is powered by batteries or the mains is irrelevant.

Since 2019, cables that are used for the transmission of electrical currents or electromagnetic fields and are designed for a rated voltage < 250V have also been covered by the RoHS Directive. Some industrially used machines are also affected by the RoHS Directive.

Exceptions include devices that serve to protect national security and some, but not all, devices for the medical sector.

An exemplary list of exceptions will be listed separately later.

Every manufacturer or his authorized representative in the EEA must ensure that the electrical products he places on the market comply with these requirements. The same naturally also applies to importers who import products into the EU and trading companies that sell products under their own trademark

As is usual in EU regulations, there are several ways of providing proof of product conformity.

One way is to establish a suitable risk management system, as described in the European standard EN IEC 63000:2018. The aim is to prove, with the support of the respective supplier, that all individual components or substances of the electrical product meet the requirements and do not exceed the various limit values.

The standard states the following: The manufacturer assesses which type of documentation is required based on the reliability of the supplier and the probability that certain components or materials violate the RoHS requirements. It may be sufficient (in the case of a supplier known to be reliable) for contractual agreements or supplier declarations to be available. However, it may also be necessary to have material declarations with all chemical compounds used or analytical test results for all components and materials.

The standard requires that the documents can be assigned to the components (e.g. via serial number, series or material definition). The quality and reliability of the documents must then be assessed. If there is a high risk, further measures, such as a separate chemical analysis, must be carried out.

We generally recommend going through a laboratory if communication with suppliers proves difficult and it is not possible to trace exactly what individual components are made of. A single contaminated solder joint is sufficient for the product to be contaminated and non-compliant.

The product is tested by means of a short test with an XRF analysis, which looks specifically at whether the substances in question may be present at all.

In this procedure, the target (product) is bombarded with X-rays. Electrons from the “outer shell” are raised to a higher energy level, causing other electrons from the inner regions to swap places with the excited electrons.

Energy is emitted in the form of element-specific fluorescence radiation, which in turn is analyzed by the detector of the XRF gun. This results in the chemical composition of the target.

If the result of the XRF analysis is negative, wet chemical testing is not carried out. However, if the result indicates bromine, for example, the product must be examined for the individual substances, which is verified by destructive testing.

The product is therefore broken down into its individual parts and examined in accordance with the specifications of the EN 62321 series of standards.

In practice, you often receive an open offer for the test, where the price is calculated on a time and material basis (XRF analysis plus additional tests).

In the European Union’s Safety Gate (or RAPEX), market surveillance authorities publish measures ordered against dangerous products so that other member states can also initiate measures against manufacturers, importers or trading companies for these products.

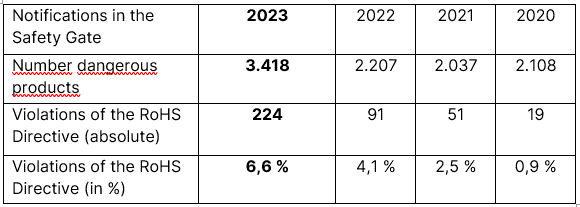

A comparison of the reports in recent years shows that the proportion of products in breach of the RoHS Directive has increased from year to year. While this figure was just 0.9% in 2020, it rose to 2.5% in 2021 and 4.1% in 2022. In 2023, 6.6% of all products were banned from sale or even recalled due to a breach of the RoHS Directive.

The products affected in 2023 include electric scooters, electric toys, LED products and USB chargers and headphones.

This suggests that the European market surveillance authorities are paying more and more attention to the issue of banned substances in electrical products.

The purpose of the RoHS Directive is to achieve a certain degree of progress in the development of products so that they can dispense with hazardous substances.

At the same time, however, there are some circumstances that justify an exemption, as the current state of the art cannot offer an alternative to the alloys or equipment concerned.

Exemplary and non-exhaustive list of some specific exceptions:

From our experience, we can say that we receive the most frequent questions on category 6 from Annex III of the Directive (lead in steel alloys) and that they are answered by us.

On March 13, 2024, the EU issued a new delegated directive that regulates an exemption for cadmium in quantum dots directly attached to LED semiconductor chips for wavelength conversion. This directive entered into force on 10.6.2024.

The two relevant entries are numbered 39a and 39b. Entry 39a is valid until November 21, 2025, entry 39b is valid until December 31, 2027.

This question is quite justified, but can be answered briefly.

Let’s start with the simple part: The so-called SVHCs (SVHC = Substances of Very High Concern), which are provided as a candidate list in accordance with Article 59, sentence 10 of the REACh Regulation, initially “only” describe the substances of very high concern for which there is an obligation to notify within the supply chain. Since the end of 2021, there has also been an obligation to register in the SCIP database. However, there is no regulation stating that a product containing SVHCs may not be sold.

Real bans, on the other hand, can be found in ANNEX XVII of the REACh Regulation (Regulation (EC) 1907/2006). In contrast, REACh and RoHS are complementary, even if there are some overlaps.

However, to avoid duplication, the EU has decided that electrical products that fall within the scope of the RoHS Directive are exempt from the proposed restrictions of the REACh Regulation.

Further details can be found here: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/5804/

In almost all countries or regions, legislators have enacted regulations similar to those in the European Union. In China, the USA, Japan, Korea and Switzerland, there are regulations that are very similar to the RoHS Directive. These are often colloquially referred to as China RoHS or Korea RoHS.

In most countries, the same substances (e.g. lead, mercury, cadmium, chromium VI, PBB, PBDE) are regulated and the limit values also correspond to the European values. In China and Japan, for example, the limit value for cadmium is 0.01% by weight. However, it is advisable to study the respective national regulations, as further requirements and labeling obligations have been included in the “RoHS”-like regulations in various countries.

There is a special feature in China. Although many of the substances mentioned are also subject to limit values here, these may be exceeded. So-called China RoHS labels are used to label affected products, which have different imprints and colors (green, orange and black). Which of the available versions must be used depends on the product in question: different labels are used depending on whether you comply with the maximum values or not. If products comply with all maximum concentration values, a green label with an “e” printed on it may be used.

The sticker is affixed to the product itself and to the packaging and signals to the Chinese authorities that the products contain “not too many” toxic substances. An orange label, on the other hand, indicates that the maximum concentration has been exceeded. Although there are no penalties or restrictions in this case, the label must be displayed.

The fact that the limit values for harmful substances are visibly exceeded for the consumer is intended to motivate manufacturers to avoid harmful substances wherever possible. In addition to different colors, the labels are also printed with a number that shows how many years the product can be used without health risk.

The idea for RoHS first emerged in Sweden when the country realized in the 1990s that many electronic products contained hazardous chemicals. If these were then to be disposed of, they would significantly pollute the environment as electrical/electronic waste.

Sweden then introduced legislation restricting the use of lead and mercury in electronic products. This Swedish RoHS predecessor was called “Blyfrihet i elektronikprodukter” (“Lead-free in electronic products”) and was introduced in 1995. Other European countries soon followed suit and began to enact similar legislation.

In 2002, the European Union (EU) proposed the RoHS Directive 2002/95/EC to ban the sale of electronic products containing hazardous chemicals and heavy metals. The European Parliament approved the directive in 2004 and the RoHS Directive came into force for the first time on July 1, 2006.

The aim of the directives was to ban problematic components from electronic waste. Some of the substances used in electrical engineering are considered to be highly hazardous to the environment. On the one hand, they have a toxic effect above certain quantities and, on the other hand, they cannot be broken down in the environment, or only with difficulty.

Among other things, the aim was to replace leaded soldering of electronic components with unleaded soldering, to ban environmentally harmful flame retardants in cable insulation and to promote the introduction of substitute products that are as equivalent as possible. Furthermore, the electrical elements and components used must also be free of the problematic substances themselves.

As European directives have to be implemented in each individual member state into their own laws, the Electrical and Electronic Equipment Act (ElektroG) came into force in Germany on August 13, 2005, which transposed the WEEE Directive into national law in addition to the RoHS Directive. A transitional period for the manufacturers and sectors affected ran until July 1, 2006

The RoHS Directive was subsequently expanded to extend the scope of the restrictions to other product categories. The extension is referred to as RoHS 2 and came into force on January 2, 2013. RoHS 2 further tightened the requirements for manufacturers and distributors of electronic devices. In Germany, the new Electrical and Electronic Equipment Substances Ordinance was created to transpose Directive 2011/65/EU into German law and the requirements of the RoHS Directive were removed from the ElektroG.

The biggest change under RoHS 2 (apart from the drastic expansion of the scope of the directive) is the strengthening of the RoHS directive into a CE directive.

Whereas RoHS 1 did not require the product to be labeled as RoHS-compliant, the manufacturer is now obliged to declare compliance with the requirements of the RoHS 2 Directive by affixing the CE mark to the product.

At the same time, a technical documentation obligation and the creation of a declaration of conformity were introduced. Manufacturers now had to prepare comprehensive technical documentation to prove that their products comply with the RoHS requirements. The declaration of conformity must also be prepared and retained.

In the past, manufacturers, importers and distributors created and used numerous RoHS-compliant logos to advertise that their products met the requirements of the RoHS Directive. As RoHS 2 makes RoHS compliance a mandatory part of EU compliance for products affected by RoHS, this is no longer permitted.

It is often the case that RoHS logos appear alongside the CE logo on current products. This shows very clearly that the manufacturers or importers have hardly dealt with the product compliance requirements.

The RoHS Directive has also been extended to include new product categories, such as medical devices and monitoring and control instruments. While the old RoHS Directive (RoHS 1) only applied to certain categories of electrical and electronic equipment (e.g. household appliances, consumer electronics, lighting, etc.), the new Directive (RoHS 2) applies to all electrical and electronic equipment. In addition, the limit values for certain hazardous substances have been updated.

A further extension was adopted on March 31, 2015 with Delegated Directive (EU) 2015/863, which expands Annex 2 of the RoHS Directive. The following four phthalates were added under the amendment, also incorrectly known as RoHS 3:

These 4 phthalates, which are often used as plasticizers in plastic or PVC, may only be contained in a maximum quantity of 0.1% in a homogeneous substance since July 22, 2019 (end of the transition period). These de minimis limits take into account that there may be very small quantities of impurities that cannot be technically prevented.

The delegated directive of 2015 also introduced a new product category. The following product categories have been affected by RoHS since then:

The new category 11 includes all other electrical and electronic equipment that cannot be assigned to any other category. Cables that are used for the transmission of electrical currents or electromagnetic fields and have a rated voltage < 250V are therefore also “electrical and electronic equipment”.

External cables that are placed on the market separately and are not part of another EEE must also be classified as category 11 and therefore comply with the substance restrictions.

What do you need to do now? Book our free initial consultation now.

Save €249!!

What do you need to do now? Book our free initial consultation now.

Save €249!!